Most people don’t spend a lot of time thinking about their ability to stay upright and balanced. Somehow, they just can. But the fact is, our balance relies on an intricate interchange between various systems in the body, the inner ear, and the brain. When balance disorders occur, they can be both frightening and extremely disruptive to people’s lives. Fortunately, proper testing can help identify the underlying cause of balance problems. And increasingly, treatments are available to help people better manage their symptoms.

Some basic facts

Balance disorders frequently take people by surprise. They often seem to appear—suddenly and without apparent reason.

Unfortunately, balance disorders can have a very negative impact on a person’s quality of life. They can interfere with the ability to work and social activities, and they can be tied to anxiety and depression. Appropriate testing, proper diagnosis, and the best possible treatment become extremely important. Of particular concern is the increased risk of falls.

Problems with balance and dizziness can occur for many different reasons. Sometimes, these issues result from:

- Damage to the inner ear from infection

- The side effects of medicines

- Concussion or head injury

- A sudden drop in blood pressure brought on by standing or sitting up quickly (orthostatic hypotension or postural hypotension)

- Cardiovascular disease

- Nerve damage in the legs

- Vision problems

- Muscle weakness

- Unstable joints

- Neurological conditions

- Anxiety, depression, and other mental health disorders

- Hyperventilation

- Problems with the inner ear

The research that AHRF funds pertains to balance disorders related to the inner ear.

The story behind balance disorders

When you stop to think about it, it’s a wonder that human beings can keep their balance at all. The human base—that is, our feet—is surprisingly small considering how tall our species is. Yet, the human body is expressly designed to move about freely and quickly in an upright position and without falling. This ability relies on various systems of the body working together in a coordinated way. It starts with a careful and vigilant channeling of information from our eyes, muscles, joints, and inner ear to the brain.

From there, the brain must quickly—and constantly—process the information so the motor and muscle systems in our legs, arms, hands, feet, and the rest of our body can respond. Our ability to then stay upright and move about also relies on the strength and health of our bones and muscles.

Sense of balance

Human beings have an innate sense of balance that depends on the healthy functioning of the inner ear. This is a very specific aspect of our overall ability to keep our balance. Sense of balance enables people to accurately perceive the relative position, orientation, and movement of their bodies and all its parts—even with their eyes closed.

Sometimes, people lose this unconscious equilibrium and develop balance problems that have nothing to do with the strength or the health of their bones or muscles. When they develop these kinds of balance problems, they may experience what most people describe as dizziness—a feeling of unsteadiness in different forms.

The sensation differs from person to person, and even from event to event. But people tend to describe it as spinning, floating, falling, rocking, or tipping over. They also may say they feel disoriented or confused, light-headed, or as if they’re going to faint.

Some people experience related symptoms like blurred vision, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or fluctuations in heart rate and/or blood pressure. Depending on the individual and the nature of the balance disorder, symptoms can last for an extended time or come and go in short bouts.

The truth is, dizziness is one of the most common symptoms people describe to their doctors. It’s very non-specific. And it can come on as a result of anything from the medicine a person is taking, to low blood pressure, to a head injury.

Many balance problems are linked to the inner ear which contains the vestibular organs. Vestibular disorders is the term for balance disorders specifically related to the inner ear—and they’re common.

Some statistics

Figures on the prevalence of balance and vestibular disorders aren’t precise, but research gives us an idea. One study found that more than a third (35%) of adults in the United States, 40 years and older, had vestibular dysfunction (2001-2004). And as people got older, the risk went up—to the point that the large majority of seniors 80 and older (85%) showed evidence of balance dysfunction. According to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), about 15 percent of U.S. adults (33 million) had a balance or dizziness problem in 2008.

Vestibular disorders often co-exist with hearing loss. What’s more, cardiovascular risk factors increase the likelihood that someone will develop one. Hypertension and frequent tobacco use, in particular, jack up the odds. But those at the greatest risk for vestibular disorders are people with diabetes. Their risk is about 70 percent higher.

The mechanics of balance

Human beings’ ability to remain upright and balanced starts with critical information being fed to the brain for processing. Three key systems are responsible for this:

- Visual (eyes)

- Somatosensory (sensory receptors found throughout the body)

- Vestibular (inner ear)

Visual

The visual system provides information about the individual’s surroundings and reads things like the distance and depth between the individual and the external physical environment that lies ahead.

Somatosensory

The somatosensory system operates independently of the eyes and ears. As part of the central nervous system, the somatosensory system relies on nerve receptors throughout the body that perceive and provide information to the brain about the state of the body. It serves several functions, including the detection of touch, pain, and temperature. Importantly, the somatosensory system also provides a sense of proprioception—that is, where the body and its respective parts are in space. Put another way, it helps with balance by keeping track of the orientation of the body and its limbs. This enables people to know instinctively where to place their arms, legs, hands, and feet while walking, running, driving, eating, and engaging in other everyday activities—without needing to consciously think about it.

The sensory receptors of the somatosensory system respond to any movement of the body by sending messages immediately to the brain. Although these receptors function throughout the body, the ones in the neck and ankles are particularly important for balance. The receptors in the neck tell the brain the direction the head is turned. Those in the ankles monitor the body’s movement in relation to the standing or walking surface. This includes providing cues about the surface condition: Is it slippery, uneven, hard, soft? People sometimes refer to proprioception as the sixth sense.

Vestibular

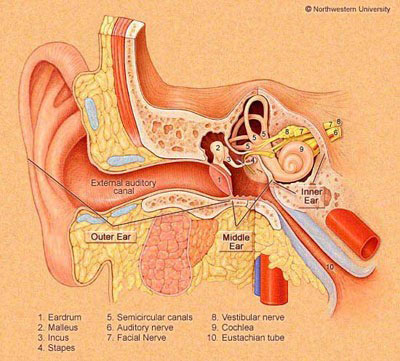

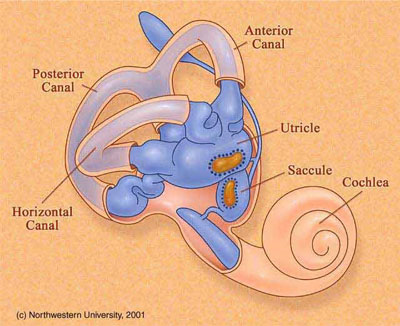

Most balance disorders are linked to the vestibular system, which is contained within the labyrinth of the inner ear. (See Figure 1.) The semi-circular canals and the otolith organs (the utricle and saccule) are the specific organs of the inner ear that must function properly for people to be able to maintain their sense of balance.

There are three semi-circular canals in each ear: 1) the anterior canal, 2) the horizontal canal, sometimes called the lateral canal, and 3) the posterior canal. (See Figure 2.) A fluid called endolymph fills each of these canals and shifts when the head changes position. When the endolymph moves, it triggers receptors in the semi-circular canals to send signals to the brain, via the vestibular nerve, about the change in the head’s position.

Each semi-circular canal detects a different directional movement. The anterior canal distinguishes nodding—the back-and-forth movement of the head. The horizontal canal monitors side-to-side movement, like when someone shakes their head to indicate “no.” And the posterior canal signals when the head tilts, like when stretching the neck by pushing the right ear down toward the right shoulder.

The otolith organs help with balance by responding to gravity. They sense linear acceleration—vertically, as in an elevator, and horizontally, as in a car. Sensory hair cells—receptors—are inside the utricle and saccule. Attached to the top of these hair cells is a jelly-like layer called the otolithic membrane. Embedded within this jelly-like layer are tiny crystals of calcium carbonate (otoconia).

These crystals are heavier than any of the other surrounding components of the ear. So, when the head tilts, gravity forces the crystals downward, causing a pull on the jelly-like layer and the sensory hair cells that it’s attached to. This pull sets off a signal from the hair cells that travels along the vestibular nerve to the brain for processing.

Other resources

For information on specific balance disorders, we invite you to visit our web page, Common Balance Disorders & More, as well as others found here.

Information on balance disorders also is available on the following websites:

National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD)

Vestibular Disorders Association (VEDA)

National Institute on Aging (NIA)

Hearing Loss Association of America (HLAA)

Learn about donating to AHRF to fund research specifically on balance disorders.