The more we learn about the human body, the more we recognize how finely choreographed its workings are. The coordinated functioning of the various systems that enable us to keep our balance is no exception. Still, our ability to remain upright and steady is more fragile than we tend to realize. In fact, there are many types of injuries, diseases, and disorders that can disrupt our sense of balance.

Vestibular disorders

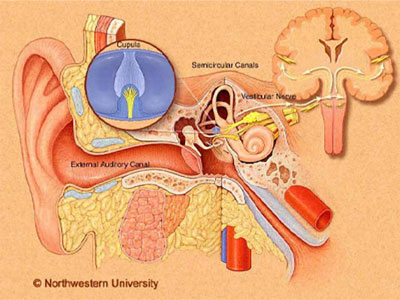

Simply explained, human balance relies on a healthy coordination of three body systems: visual, somatosensory, and vestibular. One class of balance disorders is related to the vestibular system, which reconciles information coming from different parts of our body, with input from the inner ear. Generically called vestibular disorders, these balance problems usually involve true vertigo sensations of whirling or spinning, which is distinct from other types of dizziness. Vertigo can range in severity. And it can arise through dysfunction in the inner ear and/or different parts of the central nervous system. The listing below describes a few possible causes of vertigo. Learn more about how we keep our balance by visiting the webpage Balance Disorders: An Overview.

Benign Paroxysmal Positional (BPPV)

This is the vestibular disorder most likely to cause true vertigo—the sensation of spinning when the person isn’t. Vertigo associated with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) tends to come on in response to certain movements of the head, like rolling over in bed. When crystals within the otolithic membrane of the utricle (one of the inner ear’s balance organs) break loose and shift to areas of the inner ear where they don’t belong, and if those crystals affect the flow of fluid that naturally resides in the inner ear, it causes BPPV. Hearing care professionals often can diagnose and treat BPPV with just an office visit.

Meniere’s disease

Meniere’s disease is a complicated phenomenon named after a 19th century French physician. Technically, Meniere’s isn’t a “disease” but is a cluster of symptoms whose cause can’t be tied to any identifiable disorder or health issue. Patients with Meniere’s disease experience episodes that to some degree combine true vertigo, hearing loss, tinnitus, and ear fullness. Despite a large volume of research over the past century, there are many unanswered questions about how to diagnose and treat Meniere’s disease. But research is ongoing. And there are a variety of treatments that may help to manage the symptoms of Meniere’s disease. Learn more by visiting the Meniere’s Disease webpage.

Labyrinthitis

Inflammation or an infection of the “labyrinth”—the part of the inner ear that houses our vestibular system and its components—is referred to as “labyrinthitis.” There a multiple forms of labyrinthistis, largely depending on the cause of the inflammation or infection. Because the inner ear has a role in hearing and balance function, people with labyrinthitis generally experience vertigo, along with a distinct hearing loss. As with other balance disorders, the symptoms of labyrinthitis can crop up suddenly and without warning, and symptoms of vertigo and imbalance can last up to three days. Labyrinthitis most frequently is related to a viral infection, although it can be bacterial as well. The distinction between different forms of labyrinthitis is critical for appropriate management.

Vestibular neuronitis

Like labyrinthitis, vestibular neuronitis is an infection of the inner ear. Unlike labyrinthitis, however, vestibular neuronitis doesn’t affect the auditory system, so hearing loss generally is not reported. This disease involves infection or inflammation of the vestibular nerve, which connects the balance portion of the inner ear to the brainstem. Individuals often experience true vertigo (a feeling of motion when there is no motion) and related symptoms, which can last for days, as with labyrinthitis.

Autoimmune inner ear disease (AIED)

Autoimmune disorders occur when the immune system—which normally defends against foreign cells like viruses and bacteria—becomes confused and mistakenly attacks the body’s own tissues. In the case of AIED, the immune system attacks the inner ear. Usually, this situation results in both hearing and balance problems, including vertigo, hearing loss, and tinnitus. Similar to Meniere’s disease, there are many aspects of AIED diagnosis and management that remain unclear, though research is ongoing.

Perilymph fistula

A perilymph fistula occurs when one of the fluids that normally resides in the inner ear (perilymph) leaks into the air-filled middle ear. Most often, a perilymph fistula results from head trauma, ear trauma, or barotrauma (rapid changes in barometric pressure). Sometimes, people are born with perilymph fistulas. This disorder typically leads to episodes of unsteadiness, dizziness and associated nausea, hearing loss, and tinnitus. Sometimes, with rigid restrictions of activity, the body can repair perilymph fistulas on its own. Sometimes surgery is needed.

Mal de debarquement

A rare and perplexing balance disorder, mal de debarquement (“illness of disembarkation”) comes on most often after ocean travel or some other form of prolonged rocking and swaying movement. It can follow air, train, or car travel, or even use of a treadmill, elevator, water bed, or virtual reality experience. Classically, when people are out on the water, they experience continual rocking or swaying due to water currents. Mal de debarquement syndrome occurs when that feeling continues after the physical rocking and swaying stops. Typically, the sensation is most troubling when the person is still; it decreases with passive motion, such as driving in a car. There’s no clearly effective treatment for mal de debarquement, but it often resolves within a year.

Vestibular migraine

We know a migraine to be a powerful headache that often happens with other upsetting symptoms like extreme sensitivity to light and/or sound, nausea, and wrenching vomiting. But a vestibular migraine might not include a headache. Instead of the throbbing ache of typical migraines, an extreme sense of dizziness—rocking or spinning—dominates, and the individual becomes hypersensitive to motion. Still not fully understood, vestibular migraines are more commonly diagnosed in women and in people with a history of common migraines. For more information, visit the VEDA website.

Other balance-related issues

Some injuries, illnesses, and disorders affect the vestibular system indirectly or without having originated there. Nevertheless, they can have a significant impact on balance. Described below are some examples.

Cervical vertigo

This balance disorder results from problems with the neck. The sensation of spinning characterizes cervical vertigo. Specifically, it occurs when receptors in the neck that send signals to the inner ear for balance don’t work normally. (See information on the somatosensory system here.) But interference in blood flow to the inner ear likely plays a role as well. Often the result of whiplash or other trauma that throws off proper head-neck alignment, cervical vertigo also can result from poor posture, advanced neck osteoarthritis (cervical spondylosis), blood flow problems in the arteries within the neck, and other things. Turning the head and other sudden neck movements tend to trigger the dizziness, which can last for minutes or hours. Headache, nausea, vomiting, neck pain, neck stiffness, and ear issues, such as tinnitus or pain, may accompany the vertigo. Treatment for cervical vertigo varies depending on the underlying cause and ranges from medication to physical therapy. Learn more about the neck and somatosensory system’s role in balance here. For more information, on cervical vertigo, visit the VEDA website.

Post-traumatic vertigo

Post-traumatic vertigo occurs when a blunt impact to the head or neck injures one of several possible sites of the vestibular system. These types of injuries usually result from car, motorcycle, or biking accidents, contact sports, falls, and violent assaults. Trauma to the head and neck can cause BPPV, concussions, damage to the auditory vestibular nerve known as the vestibulocochlear nerve or eighth cranial nerve, post-traumatic Meniere’s syndrome, perilymphatic fistula, and other vestibular problems. Treatment depends on the specific diagnosis—that is, which aspect of the vestibular system has been damaged. It usually involves medication and/or physical therapy, including vestibular rehabilitation and balance retraining therapy. For related information, visit the VEDA webpage on the vestibular-concussion connection.

Ear barotrauma

A rapid change in altitude is the culprit behind ear barotrauma. It happens when ear pressure doesn’t have a chance to keep up with a quick shift in outside air pressure. Most people experience it occasionally when on an airplane—particularly during descent. But it also can occur when driving through mountainous areas, when riding on express elevators, and when scuba diving. The eustachian tube helps to keep the air on both sides of the eardrum equal—that is, it keeps the air pressure in the middle ear constant with external air pressure. If the eustachian tube becomes blocked—due to a cold, for instance—it may fail to adjust the pressure within the ear quickly. This can result in a vacuum that sucks at the eardrum, stretching it inward and causing pain and other symptoms. A feeling of ear congestion and muffled hearing are the most common complaints. But dizziness and vertigo can follow—and even a perforated ear drum and lasting hearing loss. . Children, whose eustachian tubes aren’t yet fully developed, are particularly vulnerable to ear barotrauma.

Acoustic neuroma

Also known as vestibular schwannomas, acoustic neuromas are benign tumors—that is, they don’t spread to other parts of the body and are noncancerous. They appear on the vestibulocochlear nerve (eighth cranial nerve), which passes from the ear to the brain. When they’re small, acoustic neuromas typically don’t cause any symptoms. But as they grow, they can put pressure on surrounding nerves. Gradual hearing loss in just one ear is the most common symptom, along with dizziness or vertigo and tinnitus. Acoustic neuromas can cause balance problems as well as numbness in the face or ear. Although these tumors don’t spread to the brain and typically are slow-growing, if they’re left to get too large, they can exert dangerous pressure on the brain. Depending on the size of the tumor, its rate of growth, the person’s age, other health issues, and the intensity of symptoms, medical specialists may recommend watchful waiting (observation), surgical removal, or radiation therapy. About 1 in every 100,000 people develop an acoustic neuroma each year, according to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD). Over the years, the American Hearing Research Foundation (AHRF) has funded research into better understanding and treating these rare tumors.

Cholesteatoma

Cholesteatomas form when dead skin cells that normally pass out of the ear instead cluster together to form a cyst that grows within the ear. Cholesteatomas also may form when negative pressure beneath the eardrum leads to its collapse. Very rarely, babies are born with cholesteatomas. The only real treatment for cholesteatomas is surgery, which is important for avoiding serious complications. The two primary signs of cholesteatomas are discharge from the affected ear and gradual hearing loss in that ear. The longer the cholesteatoma grows, the more likely it will cause damage to the middle ear, inner ear, and surrounding bone—causing additional symptoms, including dizziness, vertigo, balance problems, and facial nerve damage. Because the cholesteatoma creates an environment that attracts bacteria and fungus, there also is a risk of developing meningitis and brain abscesses, although both are rare. Surgery cannot always remove all the cells of the cholesteatoma. Because it can come back, diligent follow-up is important. Recently, in 2018, AHRF funded research related to new techniques in the surgical removal of cholesteatomas. For more information about cholesteatomas, visit the VEDA website.

Seeking treatment

The human vestibular system is remarkably intricate, and diagnosing a balance disorder can prove challenging. The right expertise and proper testing become especially important, and multidisciplinary care can be essential depending on the cause of your dizziness. General otolaryngologists—or ear, nose, and throat specialists (ENTs)—can diagnose and treat disorders of the ear. Otologists and neuro-otologists are ENTs who get additional training to subspecialize in disorders of the inner ear, including vestibular disorders. The American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery hosts a website, ENThealth, with useful information and a search tool for finding an ENT.

Other resources

Information on balance disorders also is available on the following websites:

National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD)

Vestibular Disorders Association (VEDA)

National Institute on Aging (NIA)

Hearing Loss Association of America (HLAA)

Learn about donating to AHRF to fund research specifically on balance disorders.