Meniere’s disease (Meniere’s) is a disorder of the inner ear that sometimes seems to carry with it more questions than answers. In recent years, however, the scientific and medical community’s understanding of Meniere’s has increased significantly. Although there still is no cure, medical professionals are now better able to advise and treat people with the disorder to help them manage its symptoms.

Some basic facts

Meniere’s affects roughly 615,000 people in the United States, making it a relatively rare disorder, according to current statistics. About 0.2 percent of the U.S. population has it. And each year about 45,500 new cases are diagnosed. But despite these statistics, there continues to be debate over how common Meniere’s actually is.

Although it can come on at any age, most people with Meniere’s are 40 or older. Onset most often occurs between 40 and 60. And the probability of developing the disorder is fairly equal between both women and men, although some studies do show that women may be more likely to be diagnosed with it.

Meniere’s is called a disease, but it really is a cluster of symptoms for which the underlying cause is unknown and for which there currently is no cure.

Named after the French physician, Prosper Ménière, who first identified the disorder in 1861 as being linked to the inner ear—rather than to the brain as once thought—Meniere’s is a particularly intrusive disorder that can be difficult to diagnose.

More than anything else, Meniere’s tends to be known for the extreme and unpredictable dizziness that typically comes with it—vertigo, with which the individual is overcome by an overwhelming sensation of spinning. Other telltale symptoms come with Meniere’s as well, but it’s the intense and random vertigo that many people find the most troublesome.

The other common symptoms of Meniere’s include tinnitus (commonly called “ringing in the ears”), muffled hearing or the sensation that one’s hearing has been blocked, and a feeling of congestion, fullness, or pressure in the affected ear. Most often, Meniere’s involves only one ear, but in about 15 percent of people with the disorder, both ears are involved.

The story behind Meniere's disease

The symptoms of Meniere’s aren’t singularly unique. Nor are they uniform among everyone who has it. These two factors make Meniere’s challenging to diagnose.

Now add in that dizziness, vertigo, and imbalance are among the most common symptoms doctors are faced with diagnosing. They’re highly common across many diseases.

Yet, it’s uncertainty that really characterizes Meniere’s. The inability to specifically identify the pathology of what is prompting the symptoms of Meniere’s sets it apart as its own disorder. In other words, if all the symptoms associated with Meniere’s align AND they cannot be definitively tied to any underlying cause or disease, then a diagnosis of Meniere’s MAY be made. On the other hand, if the underlying condition or illness that is causing the symptoms can be identified, then it would not be a diagnosis of Meniere’s disease; it would be a diagnosis of something else—another disease definitively known to be causing the vertigo, for example.

Similar yet different

Part of the conundrum with Meniere’s is that it presents itself in different ways. For some people, the first noticeable sign of Meniere’s is an episode of vertigo. For others, it may be the slow progression of hearing loss, with vertigo developing later.

What makes Meniere’s such an incapacitating disorder for many is the unpredictability and intensity of what people call attacks. A typical attack of Meniere’s often is preceded by fullness or a feeling of pressure or congestion in one ear. Other people experience a change in their hearing or ringing in the ear before an attack—or both. But typically, acute episodes are dominated by severe vertigo—the feeling of spinning, which tends to come with associated imbalance, nausea, and/or vomiting. Some people also experience blurry vision, trembling, cold sweats, rapid pulse, and/or diarrhea.

The duration of these episodes varies considerably. Attacks can be relatively brief, lasting for about 20 minutes. Or they can last for many hours, even up to a day. Some people describe them as brief shocks. Others have constant unsteadiness. But most people find the attacks exhausting and need to sleep afterward.

The unpredictability

Episodes of Meniere’s may occur in clusters, with a group of attacks occurring over a short period of time—perhaps several in a week. At other times, they may come months apart. But years also may pass between episodes. In the earlier stages of the disorder, many people have no symptoms between the attacks, or they only experience mild imbalance and/or tinnitus.

As Meniere’s progresses, however, symptoms can change. For some people, tinnitus and/or hearing loss become constant. For others, balance and vision issues may chronically continue but stabilize—rather than occurring acutely with severe attacks of vertigo. But there is no rigid pattern. Everyone’s experience with Meniere’s is somewhat different.

It’s noteworthy that hearing loss related to Meniere’s often affects the lower frequencies, unlike noise-induced hearing loss, which generally starts in the high frequencies.

Drop Attacks

A particularly disabling symptom of Meniere’s, which is experienced by only some, is a sudden fall that may occur without warning and without any loss of consciousness. Typically, the individual also remembers the event.

These sudden falls are called Tumarkin’s otolithic crisis—or drop attacks. They can occur while standing or walking, with complete recovery within seconds or minutes. When these happen, people suddenly feel like they’re tilted or falling—although they may be straight. In response, they bring about much of the rapid repositioning themselves. Because they happen abruptly and without warning, the fall can result in physical injury.

It’s uncertain what percentage of people with Meniere’s experience drop attacks, but a study published in the Journal of Vestibular Research in 2018 found that 49 percent of the 602 people with Meniere’s surveyed experienced drop attacks that lasted anywhere between a few seconds to a few minutes.

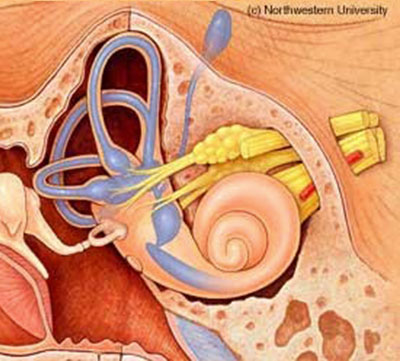

Observation suggests that drop attacks tend to be experienced in the later stages of Meniere’s and don’t affect everyone. Drop attacks are generally attributed to a sudden change within the otolith organs, which send signals to the brain regarding the positioning of the head. The otolith organs—the utricle and saccule—are located within the ear’s labyrinth. (See Diagram 1)

People also experience drop attacks due to causes other than Meniere’s—such as heart or circulation issues, or seizures. About 5 percent are due to the inner ear.

People with Meniere’s who experience drop attacks should consult a qualified physician to rule out any underlying cause unrelated to Meniere’s.

The mechanics of Meniere's disease

While the underlying cause of Meniere’s is unknown, the medical community believes it understands the mechanics of what is happening within the inner ear that triggers the symptoms. Simply, fluid builds up within the ear’s labyrinth—where the specific organs that regulate balance and hearing are found.

Under normal conditions, the membranous labyrinth (one of the two sections of the labyrinth, the other being the bony labyrinth) is supposed to be filled with endolymph—a fluid that normally circulates, stimulating receptors that signal information to the brain about body position and movement. These receptors are found in the semicircular canals and the otolith organs. (See Diagram 1.)

When someone has Meniere’s, there is too much endolymph within the membranous labyrinth, which causes swelling and issues with the normal balance signals that are sent to the brain. The result is vertigo and other symptoms.

Hearing is affected in people with Meniere’s for similar reasons. Endolymph in the cochlea normally becomes compressed in response to sound vibrations, triggering sensory cells that communicate signals to the brain where actual hearing takes place. Again, a build-up of endolymph disrupts this normal process.

Sometimes—over time—as the inner ear fills so completely with fluid, there is no space left for the fluctuation in pressure that leads to the acute attacks. For these people, the attacks may eventually taper off or even stop altogether. But the excess fluid continues to negatively affect balance and hearing—just in a more steady, chronic way.

This is because, over time, the constant surplus of fluid also can cause damage to the delicate hair cells of the inner ear that are essential for hearing. (Once these hair cells are damaged or die, they cannot be replaced.) The constant excess fluid also can shift the otolith organs, leading to changes to the normal structure of the inner ear. This can lead to chronic unsteadiness, even though the acute attacks may have dissipated.

By another name

Medically, Meniere’s is sometimes referred to as idiopathic (or primary) endolymphatic hydrops. The idiopathic label means that it arises for no known reason. It’s important to understand that elevated endolymphatic pressure isn’t unique to Meniere’s and can be caused by a number of other conditions—head trauma or diabetes, for instance. When caused by other conditions, however, it’s typically called secondary endolymphatic hydrops.

The fundamental question

With Meniere’s disease, the bottom-line question is: What is the underlying cause of the fluid build-up that is triggering the symptoms?

For other diseases and disorders, there may be a similar fluid build-up, but an underlying cause has been identified and often can be addressed.

Unfortunately, to date, the scientific and medical community has been unable to definitively identify what causes the fluid build-up in Meniere’s—or why people get it. Put another way, the question is this: What is going wrong for someone to actually develop the symptoms of Meniere’s?

Various theories abound, but nothing has been proven.

Some research has suggested that constrictions in blood vessels are the cause of Meniere’s. Others point to drainage issues due to a physical blockage or abnormal ear structure. Still others suspect allergies; viral and bacterial infections, including Lyme disease; head trauma; migraine headaches; and autoimmune responses. Because Meniere’s sometimes runs in families, others believe there may be a genetic link.

Living with Meniere's disease

It’s important for someone exhibiting the symptoms of Meniere’s to see a qualified physician to rule out other potential underlying causes of the symptoms and to get evidence-based treatment.

Otolaryngologists—or ear, nose, and throat specialists (ENT)—are a good starting point. But neuro-otologists—ENTs who subspecialize in ear disorders—are most likely to be familiar with the current diagnostic and therapeutic best practices.

Diagnosing Meniere’s

Diagnosing Meniere’s is difficult because the symptoms overlap with many other diseases and conditions. For example, dizziness and imbalance can be a symptom of anything from dehydration to hormonal imbalances, to tumors—in rare cases. So, it’s important to see a medical professional who specializes in ear disorders—with Meniere’s experience, whenever possible. This may help to minimize the time it takes to determine if the symptoms are attributable to Meniere’s or to something entirely different.

When assessing someone for Meniere’s, physicians typically will review the person’s symptoms and medical history in detail and use a number of diagnostic tests to evaluate hearing and balance. These can include a hearing test, which might be referred to as an audiometric exam; an electronystagmogram to check balance; and/or a test to measure fluid pressure within the inner ear—electrocochleography. If the doctor believes additional testing is needed to rule out certain underlying conditions that potentially could be causing the symptoms, a CT (computed tomography) scan and/or MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) may be part of the diagnostics used.

Treating and managing the symptoms

Because Meniere’s affects each person differently, physicians will suggest strategies and treatments based on the individual’s medical history, lifestyle needs, and the symptoms they’re experiencing.

Some methods for managing Meniere’s include:

- Medications to help with dizziness and shorten the attacks

- Medications to reduce the nausea

- Diuretics to help reduce the amount of fluid in the inner ear

- Dietary changes, such as limiting salt—so the body doesn’t retain as much fluid, and avoiding foods and beverages that tend to exacerbate the symptoms, such as alcohol and caffeine

- Not smoking

- Hearing aids to address any hearing loss

- Balance therapy or Vestibular Rehabilitation Therapy (VRT), which uses exercises to help people with balance issues

Additional approaches are sometimes used for more difficult cases:

- Pressure pulse treatment or the Meniett device, which is minimally invasive and designed to improve fluid flow through the ear with the use of applied pressure

- Injections of certain medications into the ear to help control the vertigo, which tends to be reserved for more severe cases that do not respond to noninvasive approaches

- Surgical procedures, which are typically used only in the most extreme cases when no other treatments help

Managing life with Meniere’s

The stress and intrusive nature of Meniere’s can take its toll, leaving people with the disorder more prone to depression and/or anxiety. It’s important that those with Meniere’s speak with their physicians about these issues and seek appropriate emotional and psychological support.

Specific types of cognitive and behavioral therapies may be helpful in managing the anxiety and/or depression that sometimes accompanies Meniere’s.

Therapies—such as Cognitive Behavior Therapy, Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, and Hypnosis—provided by qualified mental health professionals, have been helpful for some people suffering from Meniere’s and/or other disorders of the inner ear.

Each of these therapies can be used either alone or in combination.

Typically, healthy lifestyle habits tend to ease the stress that can be associated with any disorder of the inner ear. These include regular exercise—to the extent possible and approved by a physician, stress reduction, following a healthy diet, adequate sleep, and avoiding stimulants such as caffeine and nicotine.

Other resources

Additional information on Meniere’s disease can be found on the following websites:

American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS)

National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD)