Otosclerosis affects the bones of the middle ear that conduct sound. Sometimes called otospongiosis, it’s one of the most common causes of progressive hearing loss in young adults. What triggers otosclerosis is still uncertain. But it often runs in families, and experts consider it an inherited disease. Still, there isn’t always a previous family history and developing otosclerosis when a family history does exist isn’t absolute.

Some basic facts

More than 3 million people in the United States have otosclerosis—roughly as many people as in the entire state of Nevada. But the prevalence appears to be declining.

Known to have a genetic component, otosclerosis predominantly affects Caucasians of European decent, and white women in particular. In the United States, about one in 10 Caucasian adults develop otosclerosis, with the risk to white women twice as high. Generally, if someone has a parent with otosclerosis, they have a 25 percent chance of developing it as well. The risk jumps to 50 percent if both parents have the disorder, experts approximate. Otosclerosis also tends to affect people of Indian decent but is much less common among African, Native American, and other Asian populations.

Otosclerosis also tends to be a younger person’s disease. Symptoms typically crop up between the ages of 10 and 45 and most commonly during a person’s twenties. Often, but not always, the damage caused by the disorder peaks sometime in the person’s thirties. While otosclerosis can lead to severe hearing loss, it rarely results in total deafness.

People with otosclerosis often are unaware that they have the disorder until they experience hearing loss, which gradually worsens. Unlike noise-induced hearing loss—which first affects the ability to hear high-frequency sounds—otosclerosis more often causes difficulty with low-pitched, deeper sounds or whispering. Sometimes, individuals with otosclerosis speak softly because they perceive their own voices as loud. And many people with otosclerosis say it’s easier for them to follow conversations in noisy environments—perhaps because others are speaking more loudly and in higher-pitched voices. Usually, otosclerosis affects both ears, although it tends to start in one ear first.

Tinnitus, dizziness, and/or balance problems also may trouble people with otosclerosis.

The mechanics of otosclerosis

Otosclerosis involves an abnormal overgrowth of bone that prevents one of the tiny bones in the middle ear from vibrating like it should. This limits the transmission of sound to the inner ear, causing conductive hearing loss.

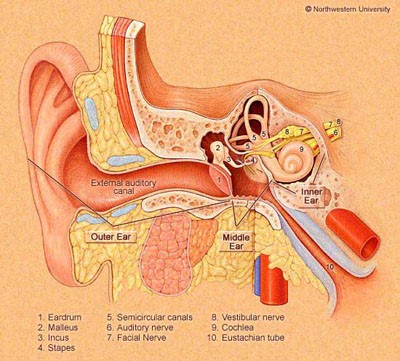

The middle ear contains a chain of three tiny bones—the auditory ossicles, which are the smallest bones in the human body. They’re the malleus (hammer), incus (anvil), and stapes (stirrup), each bearing a Latin name that describes its shape. (See Figure 1.)

Only 3 x 2.5 mm in size, the stapes is the smallest bone of the auditory ossicles, and it’s the one that otosclerosis most often affects.

All three bones of the auditory ossicles play an important role in the hearing process. For hearing to occur, sound waves must collect in the outer ear, pass through the ear canal, and cause the eardrum to vibrate. The auditory ossicles then transmit these vibrations to the inner ear, where the hearing process continues.

Right beside these tiny bones is the otic capsule, a rigid and extremely dense outer wall within the temporal bone that protects the inner ear. The otic capsule is the hardest bone in the human body.

Otosclerosis starts in this area when bone tissue of the otic capsule begins to grow abnormally. At first, the bone that grows is soft (otospongiosis). But with time, the soft areas scar and harden (otosclerosis).

When the abnormal growth and scarring of bone tissue continues and extends onto and around the stapes—or the other tiny bones of the adjacent middle ear—it limits their ability to vibrate and conduct sound, hindering the hearing process and resulting in conductive hearing loss.

Much less frequently, the scarred bone tissue from otosclerosis affects the inner ear, impinging nerve function there and resulting in sensorineural hearing loss and sometimes balance issues. Mixed hearing loss occurs when otosclerosis affects both the auditory ossicles (conductive hearing loss) and the cochlea or hair cells of the inner ear (sensorineural hearing loss).

It’s true that bone tissue in the body renews itself as part of a lifelong process known as bone remodeling. But in otosclerosis, this bone remodeling goes awry. When it continues to progress, the result is hearing loss, which typically worsens over time.

Usually, people only realize they have otosclerosis after the abnormal bone growth has reached the stapes or the other auditory ossicles, causing hearing loss. Doctors refer to this as clinical otosclerosis, meaning the person shows symptoms of the disorder. People also can have otosclerosis and never realize it because it doesn’t advance far enough for symptoms to develop. Experts call this histological otosclerosis, and it occurs more frequently than clinical otosclerosis.

The word otosclerosis is derived from Greek. It means abnormal hardening of body tissue (sclerosis) of the ear (oto).

The story behind otosclerosis

While the medical and research communities understand what happens to the ear as a result of otosclerosis, what actually triggers the disorder remains uncertain. Current thinking leans toward the belief that there is likely an interplay among multiple factors and that the genetic component may not be enough to set the disease in motion. Many experts believe that otosclerosis must be triggered by a combination of genetic, environmental, hormonal, and/or other factors.

Research suggests that otosclerosis may be linked in some way to the following:

- Genetics: Otosclerosis tends to run in families. Estimates vary, but many (perhaps up to 50%) of those with the disorder have a gene linked to it. Statistics also show that there’s a 25 percent chance of developing otosclerosis if one parent has it and twice that (50%) if both parents have it. But questions remain: Why doesn’t everyone with a family history of otosclerosis get it? And why do some people with no family history of the disorder develop it? Research continues to identify and better understand the actual genes involved in otosclerosis.

- Pregnancy: There appears to be a pattern in which women first show signs of otosclerosis during or immediately after pregnancy. For these women, hearing loss seems to come on more rapidly. In fact, women with otosclerosis in both ears felt they experienced a 33 percent decline in their hearing after a single pregnancy, one study found. Study participants also noted greater decline with each subsequent pregnancy. Experts theorize that hormonal changes during pregnancy may worsen the otosclerosis.

- Measles and/or other viral infections: Some experts believe there may be a viral link to otosclerosis and to the measles in particular. They suspect that the viral infection triggers the disorder. Research conducted on bone and tissue samples taken from the ears of people with otosclerosis has found evidence of the measles virus, although not in all samples. In addition, studies show a significant decrease in otosclerosis among people vaccinated against the measles.

- Trauma and stress fractures: Experts have suggested that stress fractures to bones in the ear, and to the bony tissue surrounding the inner ear in particular, may put people at an increased risk of developing otosclerosis.

- Autoimmunity: Some researchers believe that otosclerosis may be linked to an autoimmune response by the body. This type of response generally happens when the person’s immune system becomes confused, acting against healthy body tissue as if it were a pathogen. Frequently, environmental and genetic factors play a role in the activation of an autoimmune response by the body.

Clearly, otosclerosis is a complex disease. And both the intricacy and relative inaccessibility of the inner ear raise additional challenges in fully understanding it.

Living with otosclerosis

When a young person begins to notice they’re losing their hearing, it can be a very confusing and overwhelming time. It’s very important that they seek appropriate medical counsel to get an accurate diagnosis.

Anyone who experiences hearing loss should see an otolaryngologist (an ear, nose, and throat doctor, or ENT), otologist, and/or audiologist.

If the person experiences low-pitched hearing loss, falls within the demographics of those at greater risk of otosclerosis, and/or is aware of hearing loss in any member of the extended family, they should ask the hearing health provider about otosclerosis specifically and about their experience in diagnosing it.

Diagnosis typically includes a review of the person’s medical health and family health history, the hearing care professional taking a look into the ear canal with a hand-held magnifying light called an otoscope, hearing tests, and sometimes, a computerized tomography (CT) scan. Ruling out other health issues that potentially could cause the same symptoms is an important part of the diagnostic process as well.

Current Treatments

Treatment for otosclerosis depends on the person’s specific circumstances, the degree of the symptoms, and decisions made together by the doctor and individual.

Different approaches that have been used to treat and/or manage otosclerosis include the following:

- Watch and wait: Otosclerosis will progress to different degrees and at different rates for different people. Not everyone with otosclerosis goes on to develop moderate to severe hearing loss. For some, the disorder may progress at a much slower rate. Depending on the degree of hearing loss, the person’s health, and other individual factors, hearing care professionals may recommend a watch and wait approach. This typically includes testing the individual’s hearing regularly.

- Hearing aids: Many people with otosclerosis use hearing aids to help compensate for the hearing loss. Hearing aids amplify sound and can be programmed to the specific hearing needs of the individual. New models also provide many useful features. Licensed hearing care professionals can coordinate with the individual’s physician and advise the person with otosclerosis on hearing aid types and technologies that are most appropriate for their individual needs. In addition to hearing aids, there may be supplemental assistive devices that can help people with otosclerosis hear better in their day-to-day lives. Qualified hearing healthcare professionals can guide individuals on the usefulness and appropriateness of such devices.

- Sodium fluoride supplements: Some doctors prescribe these dietary supplements in certain doses and according to specific schedules in the hope of slowing the progression of the disease. Due to limitations in existing research, however, experts continue to debate the effectiveness and appropriateness of using these supplements.

- Surgery: The doctor may consider a specialized surgery known as a stapedectomy when the otosclerosis has progressed to a certain point. During this procedure, the surgeon removes the stapes affected and replaces it with a prosthesis—an artificial stapes—designed to serve the same function in the hearing process. Specialists consider many individual factors before recommending this surgery.

Currently, there is no drug treatment for otosclerosis. But research continues with the goal of one day developing safe and effective pharmacological therapies to treat the disorder.

Managing life with otosclerosis

Otosclerosis can be a very difficult disorder for a young person to grapple with, and for some, there’s no forewarning of family history. People with otosclerosis should speak with their physicians about the challenges they’re facing and seek appropriate professional support. Following a healthy lifestyle generally helps people better manage the stress associated with any hearing disorder. This includes stress reduction, regular exercise—to the extent possible and approved by a physician, a healthy diet, adequate sleep, and avoiding nicotine and other unhealthy substances. Generally, addressing any type of hearing loss tends to improve quality of life.

AHRF’s early roots in otosclerosis research

AHRF’s earliest beginnings started with research to improve the lives of people with otosclerosis.

In 1938, AHRF’s founder, Dr. George E. Shaumbaugh, Jr. (1903-1999), was instrumental in developing and performing a groundbreaking surgical technique called fenestration. Fenestration restored hearing specifically to people with otosclerosis. Together with Dr. Julius Lempert (1890-1968), Shaumbaugh performed the first-ever successful operation to restore hearing, using this technique.

Fenestration led the way to more advanced techniques and has now been replaced by stapedectomies. Once again, researchers associated with AHRF helped further develop these leading-edge procedures.

Since those early beginnings, AHRF has played an important role in moving the medical community’s understanding of otosclerosis forward. The Foundation continues to accept applications for research grants for the study of otosclerosis and other disorders of the inner ear.

Other resources

Additional information on otosclerosis can be found on the following websites:

National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD)

Otopathology Laboratory at Massachusetts Eye and Ear/Harvard Medical School

The National Temporal Bone, Hearing and Balance Pathology Resource Registry

Hearing Loss Association of America (HLAA)

Learn about donating to AHRF to fund research specifically on otosclerosis.